NEWS

The jail visit that rescued Mpho Makola’s career

When Mpho Makola was 17, his mother did something almost unthinkable but overly effective. As a teenager, exploring all things permissible and forbidden, the man popularly known as Bibo was fast losing his moral compass.

Straight after school, he’d throw his bag on the bed and join the kind of crew any mother would take exception to. They would sit by a famous corner in Alexandra, a township near the upper-class suburb Sandton, and smoke all sorts of smokable things.

WRONG CREW

“I was in the habit of chilling out with the wrong crew. My aunt called my mother and told her all about it. I’d also started smoking dagga,” Makola recalls.

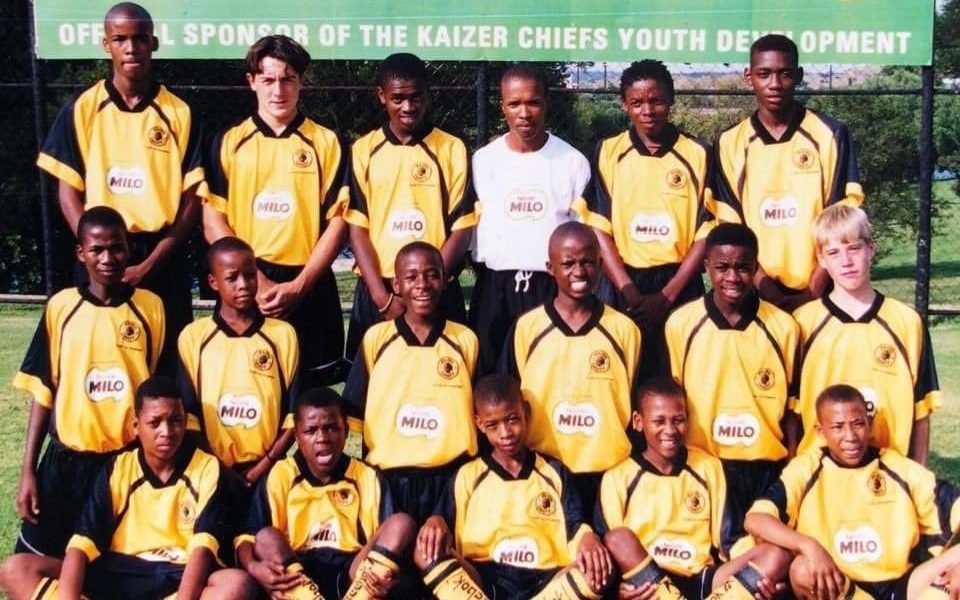

Surprisingly, his footballing future looked brighter after a stint with Kaizer Chiefs’ development side.

Bibo cut his football teeth at Vaal Killers, which played in the Chappies Little League, from as early as six.

But that stint with Amakhosi’s juniors set him on the pedestal. Of course, it started in an unspectacular fashion. The tiny lil’ boy from ‘Gomorrah’ was initially turned away because there were too many players in the Chiefs junior side.

But Lebogang Charles Ndebele, the Under-17 coach, had to beg the Under-15 coaches to give this 13-year-old a chance.

“They had turned him away, and I felt for the poor boy. I felt bad,” Ndebele says emphatically.

For Ndebele, affectionately known as Chief in football circles, the most significant thing this scrawny-looking teenager had done was save money to attend the unplanned trial in Milo Park.

“He was only allowed to train with the team because he had come, and we couldn’t let him leave without playing. I remember we played Rondo [a type of game similar to keep away that’s used as a training drill in football], and I saw his good touches and football brain. I decided I’d help the boy,” Ndebele adds.

MPHO MAKOLA WAS UNTOUCHABLE

Exactly a fortnight later, Ndebele invited Makola to his Under-17 side for a friendly match because some players were away preparing for exams.

“The boy was buzzing in that friendly match. He was untouchable, and everyone loved him. That’s how Mpho was signed at Chiefs,” Ndebele reveals.

But four years later, his journey with the Phefeni Glamour Boys ended abruptly. It cut short his hopes of one day pulling on the black and gold shirt. This was after he refused to sign a professional contract, which would, however, see him continue in the junior set-up.

“I knew that contract would bind me, and I’d be stuck in the development team. I wanted to play senior team football,” Makola says.

And so, he joined Alex’s amateur side, Sheffield United ekasi. But that came with all sorts of negative influences that were fast driving him off the rails.

He admits that it could have gotten worse if his mother was any other ordinary mom. But his no-nonsense mom, Joyce Makola, raised him single-handedly, is a cop stationed at the Bramley Police Station.

THE TRAUMATISING TOUR

After hearing of his shenanigans in Alex, where he was staying with his aunt, she invited him for a lil’ pep talk. But it was not the usual verbal pep talk. A traumatising tour of a police holding cell in Bramley accompanied it. The sight of confined and caged young men, some that looked as young as him, was enough to knock some sense into his head.

“He was hanging around with the wrong company in Alex, so I decided to take him to a jail cell to show him what awaited him if he chose the wrong path. I showed him how people lived in the holding cells and what they ate,” she says.

Interestingly, Makola admits that was his turning point. It was an unpleasant experience that gave him the necessary wake-up call. He would instead learn from his cop mom than learn the more complicated way behind cells.

“It made a significant impact on me because I thought my mom worked hard to be where she was, and to see her being so emotional, down and being so concerned about me was touching,” he says, adding that his mom started as a hairdresser.

Sadly, he reveals that some of the crew he chilled with by that infamous corner are either dead or in prison.

BEGGING FOR A FEW RANDS

Dominantly, the dead and incarcerated were involved in botched car hijackings, a crime he could have quickly been roped into had he continued with them. And then you have those who are doomed, begging for a few Rands each time they see their star footballer friend.

His Sheffield coach Thabo Malebjoe vividly remembers the jail visit’s impact on his prodigy.

For Malebjoe, there was also an extra motivation to help his young Turk stay out of trouble. Makola’s plainspoken mom had threatened to arrest him. Yes, she would also throw his coach into the cells if he was misleading her son.

“At one point, his mom didn’t want him to stay in Alex. She thought he was coming to be mischievous. She threatened to arrest me with Bibo. But the jail cell visit changed him,” Malebjoe says. He adds that after the Bramley police visit, he saw a determined ‘Bibo’.

His mother proudly remembers how he’d bring half his man-of-the-match earnings after that jail visit.

“I started to understand he had potential because often he’d be man-of-the-match, and he’d get money for it. If it were R1000, he’d give me R500,” Mama Joyce says, adding that she was never interested in football.

By his admission, he played some of his best amateur football at Sheffield. And his ingenuity in the middle of the park did not go unnoticed with several trial stints at Ajax Cape Town, Santos and later Mamelodi Sundowns.

CHIEFS DEMANDED COMPENSATION

“At Ajax, I scored in a friendly, and they wanted to sign me, but Chiefs demanded compensation. Ajax refused to pay, and I went back home and told myself I’d not go back to Chiefs,” Makola says.

Malebjoe recalls the unsuccessful Sundowns trial, organised by Brian Baloyi, who also hails from Alex, for two reasons. They had a breakdown driving back from Chloorkop, and the 19-year-old boy got him all emotional and teary as he expressed appreciation for all his help.

“He said to me, ‘coach Thibos, you’ve helped so many young boys ekasi, but I doubt you’ve done more for anyone than me. Many of these boys have forgotten you, but I can assure you – I’ll never forget you.’ I couldn’t say a word after that. I had to hide my tears,” Malebjoe says admiringly.

True to his word, Makola has never forgotten him. In fact, his former coach says there’s been a reversal of roles – the Cape Town City midfielder is now playing mentor to the man who was instrumental in his development.

His last port of call before his PSL breakthrough was Harold ‘Jazzy Queen’ Legodi’s Africa Sport Youth Development Academy in 2007. At the time, the academy was also home to Patrick Phungwayo, Lehlogonolo Masalesa and Oupa Manyisa.

ALMOST QUIT

Growing frustrated as his teammates were securing moves to PSL sides, Makola discloses how he almost called it quits.

“I was on the verge of giving up. My mom suggested that I go back to school. But I looked at my medal cabinet. I was an amateur player, but I kept collecting medals everywhere I played,” he says, adding that he had already applied for a place at the Tshwane University of Technology.

Luckily, he hung on a little and put up a five-star performance in the Walter Sisulu Tournament in December 2007.

“I didn’t know there were scouts from Free State Stars, and I scored three free-kicks in one game. Jazzy didn’t tell me I’d secured a trial at Free State Stars until January,” he says.

There was beginning to be a ray of sunlight. The future was looking bright, all thanks to that one jail visit.

RELATED STORY: Of Mpho Makola’s four-year stint with Kaizer Chiefs

Source Link The jail visit that rescued Mpho Makola’s career