Mzukisi Ndara purchased what he thought was a new car in 2004, but it turned out to be a used one with extras he did not ask for.

Former Department of Health communications executive Mzukisi Ndara may turn out to be that one customer – to paraphrase Clint Eastwood from the movie Gran Torino – you probably shouldn’t have messed with.

In 2004, while still a government employee, he purchased a 2004 Nissan X-Trail, believing he was getting a 2.2 litre diesel manual demonstration vehicle. It later turned out to be a used vehicle, though he was charged for a new X-Trail 2.5 litre petrol automatic, as well as extras that were non-existent.

The vehicle was financed by WesBank.

He has been on a 21-year quest for justice, an astonishing investment of time and money over a vehicle costing R297 990.

As Moneyweb previously reported, the ‘new’ vehicle he purchased was actually a demonstration model with several thousand kilometres on the clock, which means it should have been discounted to R270 000. Included in the sales price were ‘fictitious’ extras valued at R35 340.

His case has been defeated at the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) and twice at the Constitutional Court (ConCourt). For most people, that would be the end of the legal road. Not for Ndara.

He has now served papers in the ConCourt against the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, the head of the office of the Chief Justice, and a host of officials at the court.

He is taking on the highest court in the land, arguing it has failed in its duty to uphold the Constitution and its own rules.

He wants the court’s denial of his application for leave to appeal an SCA ruling, as well as a rescission application against him, to be set aside on the grounds of procedural irregularities.

In his papers before the ConCourt, he raises questions others at the losing end of justice have similarly asked: given the ConCourt’s required leniency for lay litigants, why was his application rejected by the court registrar with a demand that he file a new one to be addressed to the registrar? On whose authority, and what is the legal basis for this?

ALSO READ: WesBank customer’s 20-year quest for justice is now before the ConCourt

J’accuse

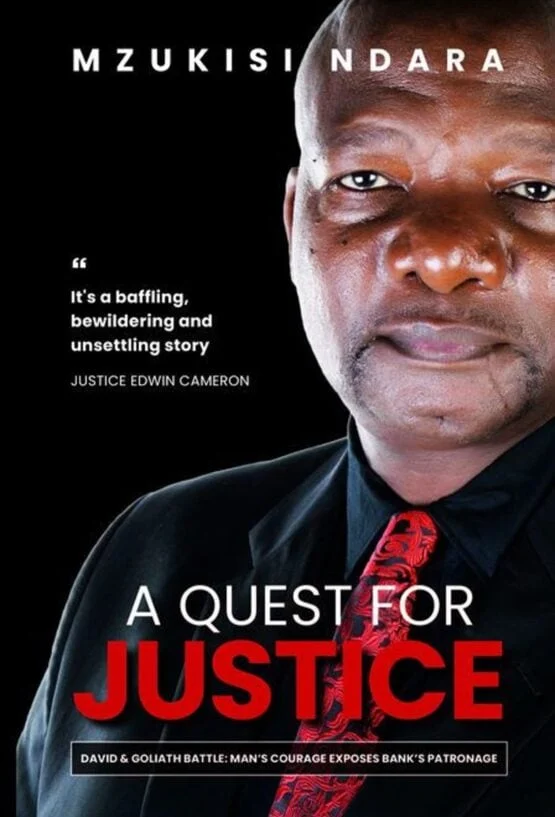

He wrote a book about it, which won heavyweight endorsements from retired Constitutional Court Judge Edwin Cameron and former public protector Thuli Madonsela. In 2018, the National Director of Public Prosecutions also endorsed Ndara’s version that “WesBank and its employees breached the contract in the form of misrepresentations and also acted in violation of various statutes”.

The case is riddled with irregularities and fraud, according to Ndara’s voluminous papers before various courts. The offer to purchase contained only the signature of the dealer’s representative. That renders it a fraud, he asserts, and fraud unravels all agreements.

Ndara was charged interest at prime plus 4.5% instead of the prime less 2% to which he was entitled to as a government employee.

The case has ping-ponged from the lower courts to the SCA, and was earlier this year dismissed by the ConCourt. Ndara went back to the ConCourt to have its judgment rescinded. That, too, was rejected.

WesBank previously told Moneyweb that its position had been affirmed by the ConCourt, which, in its view, supports the bank’s position. The case had been heard in various courts over the years, and all have dismissed Ndara’s claims.

“The merits of my case have yet to be heard,” says Ndara.

He’s had some victories along the way, such as the Eastern Cape High Court’s 2014 dismissal of WesBank’s attempt to dismiss his case, and the 2018 setting aside by the same court of Ndara’s leave to appeal a ruling against him, which had been obtained in his absence.

ALSO READ: Ground-breaking judgment rules that bank is responsible for defective bakkie it financed

The case has been defeated on technical issues, such as argument over prescription (that he waited too long to being the matter before court), but he has managed to keep it alive.

All of this has come at a cost of probably over R1 millions in legal fees – though Ndara drafted the last three applications himself without employing attorneys or advocates. All this over a car costing R279 000.

That’s not counting the less visible costs: his late wide Unathi wife passed away from depression because, he says, of the family’s deteriorating financial position. He was blacklisted by the banks and lost two houses as a result. Then he lost his government job.

Why does he continue?

“I decided I have to test whether the laws in SA actually protect the consumer or the banks. Sadly, I have found they protect the banks. This cannot be allowed to stand. It’s a perversion of justice.”

The law allows for cases to be escalated where the court registrar interferes with an application by refusing to issue, accept or place a matter before a judge. This is what Ndara says happened in his case. He says his application stands unopposed as none of the respondents filed notices to oppose by the 19 December deadline. He is now awaiting the court’s ruling.

ALSO READ: High court agrees with Consumer Tribunal’s R100 000 fine for used car dealer

Precedents

Last week, in a not dissimilar case, the SCA ruled against FirstRand and in favour of Aletta van Niekerk after she purchased a 2012 Ford Ranger in December 2017 from Autorama in Klerksdorp, North West province, only to find out four days later that vehicle came with a faulty oil cooler and gearbox. The gearbox was replaced, but within two months the car overheated again.

Van Niekerk paid a deposit of R150 000 by way of a trade-in, leaving a balance of R268 180 to be financed by way of 72 equal monthly instalments of R3 724.

Given the problems with the vehicle, Van Niekerk formally cancelled the agreement by addressing a latter, through her attorney, to the dealership and the bank. The bank rejected the cancellation.

Van Niekerk took the case to the high court, which ruled that she should have cancelled the agreement with the bank when the defective gearbox was first discovered. The bank contended that it was not the supplier of the vehicle.

The SCA disagreed, ruling that Van Niekerk was entitled to cancel the agreement, that the high court misdirected itself in ruling that the Consumer Protection Act did not apply (and that he had not exhausted other remedies available to her under the Act), and ordered the bank to refund her R170 023 plus interest and pay her legal costs.

“There are several other cases, some from the SCA, affirming that when you are buying a vehicle, you are buying from a bank,” says Ndara. “That is all I am asking from our justice system.”

This article was republished from Moneyweb. Read the original here.