It is impossible to tell the story of how the business of broadcasting has evolved in South Africa without examining the industry’s political aspects.

Political influence played a role in the South African broadcasting landscape even prior to the first broadcast going live on 5 January 1976. The conservative government of the time saw the “devil’s box” as a threat to its value system, leading to South Africa being a relatively latecomer to broadcasting by international standards.

This is the fourth in a series of articles TechCentral is publishing this week to mark the anniversary of the launch of television broadcasting in South Africa on 5 January 1976. Visit our homepage for more.

Consequently, when the industry finally took off in 1976, state control and censorship were the name of the game. This put big limitations on the type of content that would end up in people’s homes.

All television content, including news, sports and entertainment, was limited to the SABC. Though the broadcaster built infrastructure, including in-house studios and filming equipment, along with the necessary skills, internally, viewers were not treated to much variety.

There was one antidote to the monotony, but only in a relatively small part of the country. Residents of the what is now North West could enjoy a more liberal line-up of local and international TV shows on Bophuthatswana’s Bop TV. Some residents on the western outskirts of what is now Gauteng could access Bop TV signals spilling over from Bophuthatswana.

The first real gamechanger for South African broadcasting came with the introduction of M-Net in 1986. It was the first time that South African viewers outside of the Bantustans had an alternative to state broadcasting. Most significant was M-Net’s business model, which relied on user subscriptions and advertising revenue instead of the national fiscus.

With competition came innovation, with M-Net pioneering South Africa’s first daily soap opera, Egoli: Place of Gold. Carte Blanche, launched in 1988, introduced a standard for investigative journalism not seen on state programming at the time. A small segment named SuperSport would eventually grow into one of the largest broadcasters of live sports in the world.

Liberalisation

M-Net’s entrance into the market led to some market liberalisation, but most South Africans still relied on the SABC for their programming – and M-Net was precluded from offering its own news service. However, a transformation was brewing at the SABC, too. Brand Fourie, who had led the broadcaster from 1985, was replaced by Christo Viljoen, an academic and electronics engineer.

Viljoen brought in a strongly commercialised team that included the likes of Quentin Green, Gert Klaasens and Wynand Harmse. The trio would form the Viljoen Task Group on Broadcasting, leading to a 1991 report recommending the deregulation of the airwaves and the introduction of community radio, among other radical changes.

Read: Television at 50 | The broadcast that changed everything

“That is an often-overlooked but important turning point, especially from a business point of view, because what that team did was shift the focus of the broadcaster from simply being a state propagandist to being a more organised commercial and entertainment provider,” said Ruth Teer-Tomaselli, a renowned telecommunications author and emeritus professor of culture, communications and media studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

The next major change would come in 1993 with the formation of the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA). According to Teer-Tomaselli, the IBA was formed prior to South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994, partly because preparing the SABC for the election was one of IBA’s first major tasks.

The IBA delineated broadcasting licences according to public (SABC), commercial (M-Net) and community categories. By 1997, regulations on quotas for local television and music content on South African radio and TV were introduced. Teer-Tomaselli said these regulations had a tremendous impact on the development of independent production houses in South Africa because they also stipulated that some of the content must be produced external to the broadcasting houses.

“By the early 2000s, the SABC had practically shut down all of their internal production, except for sport, a little bit of education and news production. They don’t make dramas anymore because that is all commissioned,” said Teer-Tomaselli.

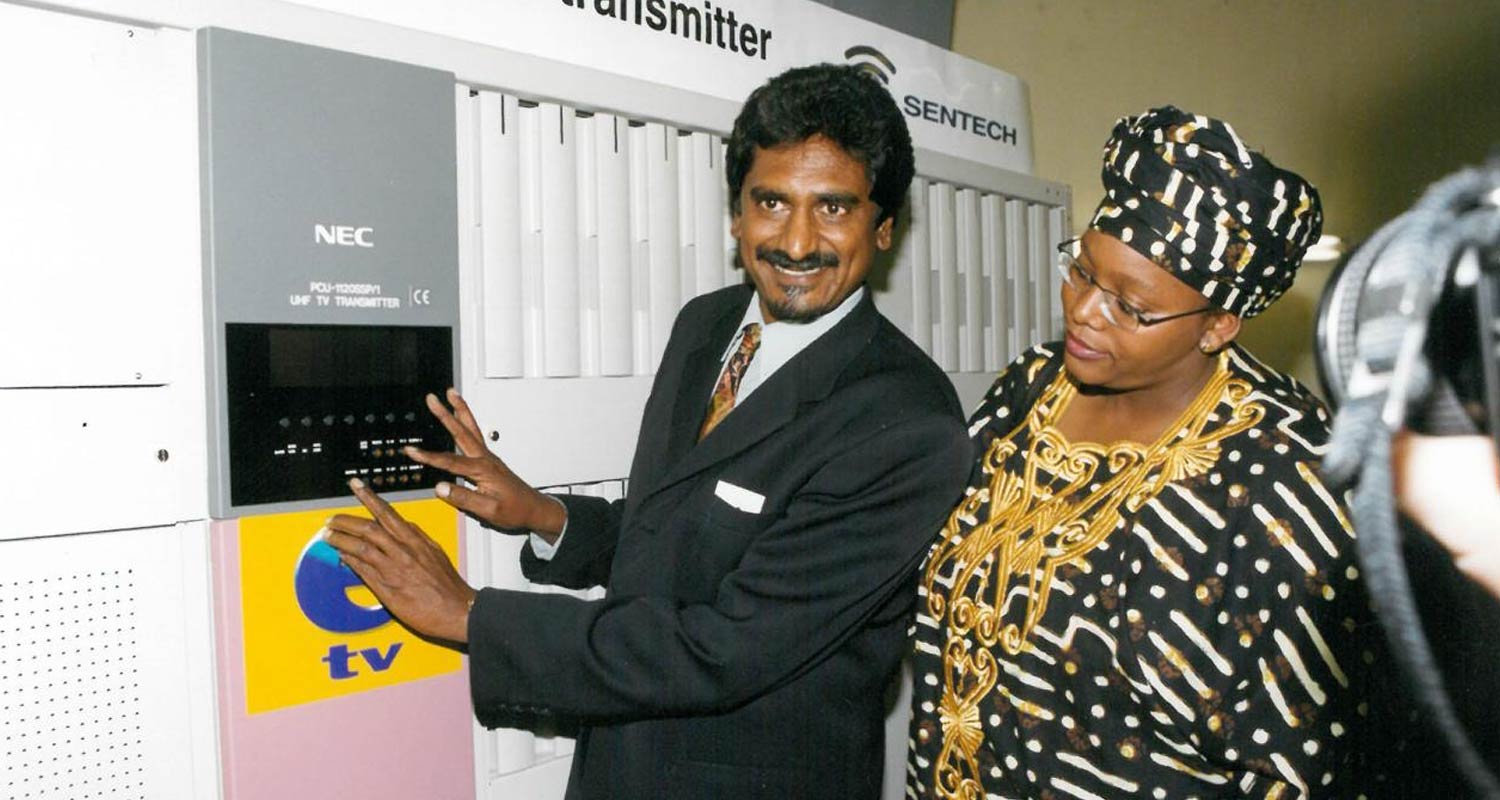

Another major development would further impose radical changes to South Africa’s broadcasting landscape before the turn of the century. Following a fiercely competitive bidding process in the years prior, the Midi TV consortium was granted a broadcasting licence by IBA, leading to the launch of e.tv in October 1998.

E.tv further liberalised the market by introducing a completely new broadcasting model that encompassed elements of the incumbents at the time. Like the public broadcaster, e.tv was free to air, but it was also privately owned, like M-Net. Its launch introduced new competitive dynamics into the broadcasting landscape, even forcing the SABC to rebrand shortly prior to its launch in an effort to defend advertising market share.

E.tv also came with independent news and current affairs shows like 3rd Degree, along with a slew of newly minted soap operas such as Backstage, Rhythm City and Scandal. The boom in local content production led to flourishing production houses such as Quizzical Pictures, Ochre Moving Pictures and Urban Brew Studios.

With the new millennium came new technology, and the decade between 2000 and 2010 would see the internet rise in prominence as the cornerstone technology facilitating world commerce.

Rise of streaming

The launch of social media platforms, such as Facebook in 2004 and YouTube in 2005, pointed to a new era of media consumption. By 2007, Netflix launched with only a thousand titles available for streaming – that number has grown to around 14 000.

South Africa’s broadcasting industry has lagged behind on digitisation. Although M-Net evolved into DStv as far back as 1995, effectively introducing satellite-based digital television to South Africa, parent company MultiChoice’s streaming service Showmax is struggling to garner market share against larger international rivals.

The SABC’s digitisation journey has been hampered by perennial delays to the broadcast digital migration project. Many in the industry, including Teer-Tomaselli, believe government’s decision to adopt digital terrestrial television in 2010 was short-sighted. The SABC has launched its own streaming service, SABC Plus, and e.tv has the eVOD streaming service to compete with the streamers.

Read: Television at 50 | How the SABC lost its way – and what it must become

“DTT only made sense at the time because it was based on short-term economic thinking instead of long-term vision. Government really didn’t believe that the internet would be so powerful so soon,” said Teer-Tomaselli. – © 2026 NewsCentral Media

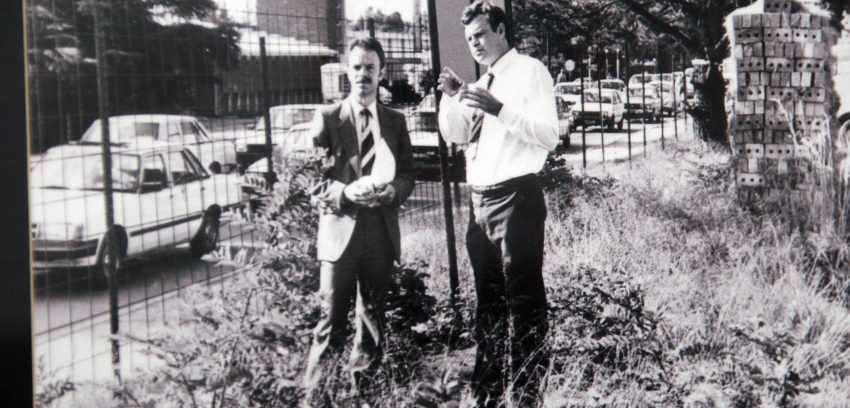

- Main image: M-Net’s first chief technology officer, Jock Anderson (left), with co-founder Koos Bekker at the site in Randburg, Johannesburg where MultiChoice Group’s head office is located today. Image courtesy of MultiChoice.

Get breaking news from TechCentral on WhatsApp. Sign up here.