Policyholders drew an average of 5.6% of their invested capital as income in 2024, down from 6.6% the previous year.

Living annuity investors in South Africa reduced their income withdrawals to the lowest average level on record in 2024.

According to data from the Association for Savings and Investment South Africa (Asisa), policyholders drew an average of 5.6% of their invested capital as income in 2024, down from 6.6% the previous year. It is the lowest average since Asisa began compiling living annuity statistics in 2011.

Since 2010, Asisa has encouraged its member companies to submit annual living annuity statistics, with the first set of data collected in 2012 for the 2011 reporting period.

Jaco van Tonder, deputy chair of the Asisa Marketing and Distribution Board Committee, told Moneyweb that about half of the drop in drawdowns is due to market performance over the past year.

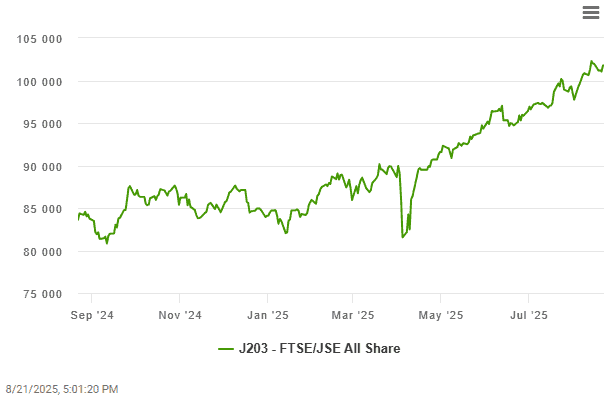

“If you do the maths and add the returns of the JSE All Share Index to the asset pool – and assume the previous drawdown rate was, say, 6.5% – the increase in assets reduces the effective [drawdown] rate.”

The FTSE/JSE All Share Index (Alsi) delivered a return of 13.4% over the 12 months to 31 December 2024. Over the 12 months to the end of June 2025, the Alsi delivered a return of 25.2%.

Asisa’s statistics show that the living annuity asset pool grew to R781.7 billion by the end of December, compared to R682.2 billion in the corresponding period in 2023.

The number of living annuities increased from 535 509 and the end of 2023 to 554 043 as 31 December 2024.

ALSO READ: Tax-free savings account still the best way to save

‘Shift in behaviour’

While half of the lower drawdown rates can be attributed to market growth, Van Tonder believes the “other half” is due to investors within the measured pool choosing lower drawdown rates – whether they are existing annuitants or younger retirees opting for lower income levels.

“We can’t tell from the data if one particular group of investors is driving this shift.”

Van Tonder mentions three factors that determine whether a living annuity will sustain income for life – the drawdown rate, investment performance, and the lifespan of the retiree.

He believes annual drawdown rates of 4% to 5% in the first decade of retirement, and below 8% later, provide the best chance of preserving purchasing power.

The Asisa data reveals that more investors are now keeping within those ranges. By the end of 2024, 36.4% of assets (R284.4 billion) were in the 2.5% to 5% income band, while 23% (R179.9 billion) were in the 5% to 7.5% band.

Van Tonder says this represents a positive trend, showing increased awareness after years in which living annuities were often used to stretch limited savings. He believes guidance from product houses, along with articles in the media, has made investors more mindful of prudent drawdown levels.

More people also get financial advice before retirement, which helps to set boundaries, he adds.

“This means people are more realistic about the income they can withdraw. This leads to better decisions, and it’s visible in the lower drawdown rates.”

He cautions that investors should resist increasing their drawdown dates on the next policy anniversary date, so that they can lock in some of the investment gains from last year and this year.

ALSO READ: Planning for retirement? Consider these key risks

Risks that erode retirement savings

Notwithstanding the better awareness, Van Tonder cautions that risks to sufficient retirement savings persist – particularly low early-career saving.

“It’s important to talk about retirement early, so people understand how their decisions now affect their future income,” he notes.

The “winning” formula for saving for retirement is for people to put away 15% of their income for 40 years, which will mean they will retire on about 75% of their final salary.

“But young people often start with minimal contributions of 5% per year because they argue it won’t matter much, as their salaries are small. Or, they just don’t save for retirement at all if they are not compelled to do so in the early years.

“Our calculations show that skipping contributions during the first decade halves the eventual pension, even if you contribute for the following 30 years. People underestimate the exponential effect of compound interest, but it’s the most powerful driver over time.”

Van Tonder cautions that the two-pot system, which came into effect in September 2024, could also undermine retirement savings if people withdraw everything in the savings pot every year.

“This could effectively cut your contributions to 10%.”

ALSO READ: Two-pot retirement system: How to maximise your tax benefits

The two-pot system in fact comprises three components – a savings pot, a retirement pot, and a vested pot.

Members may access their savings pot once a year, provided it holds at least R2 000 plus fees. The retirement pot, which makes up two-thirds of contributions, must be preserved until retirement, after which the funds are annuitised.

What also erodes retirement savings, says Van Tonder, is the fact that fund members may withdraw all their retirement savings from the vested pot (containing contributions until 31 August 2024) when they resign.

This article was republished from Moneyweb. Read the original here.