Thanks to a change in global supply dynamics and good monsoon rains, with higher stock levels expected to persist this year.

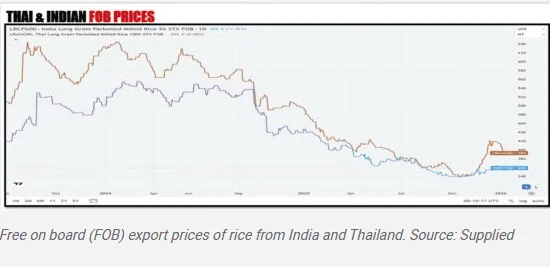

Global rice prices look unlikely to recover soon as oversupply continues to weigh on the market, dragging prices down from about $600 (R9 693) a tonne to around $350-$360 (R5 654).

South African consumers are already seeing lower rice prices on supermarket shelves, with all major retailers currently offering rice on special as global prices ease.

South Africa imports 100% of its rice requirements – typically between 1.2 million and 1.3 million tonnes a year – with most of it sourced from Thailand, India, Pakistan and Vietnam, says André van der Vyver, executive director of the South African Cereals and Oilseeds Trade Association (Sacota).

“Lower rice prices come after a period of synthetically higher prices, due to India’s decision to restrict rice exports ahead of its national elections,” he tells Moneyweb.

“As one of the world’s largest exporters, India’s move constrained global supply and lifted prices across international markets.”

Once the restrictions were lifted after the election, exports resumed into a market that had already responded by expanding production elsewhere, resulting in a swing to surplus.

According to Van der Vyver, good monsoon rains have further bolstered output and higher stock levels are expected to persist this year.

This is illustrated in the price graph below, which shows rice prices peaking above $600 a tonne before declining steadily over the past 18 to 20 months.

The graph highlights how quickly prices adjusted once export flows normalised.

ALSO READ: Food basket price up again, raising questions about producers and retailers

No rice production in SA

There is no meaningful rice production in South Africa, despite past attempts at cultivation on the Makhathini Flats in KwaZulu-Natal.

“Historically, rice production has been associated with heavy water usage,” Van der Vyver says.

Rice-producing countries typically rely on flood irrigation, which makes it unsuitable for cultivation in a water-scarce country such as South Africa.

Rice enters South Africa mainly through Durban harbour and is distributed by groups such as Premier Foods, PepsiCo and Tiger Brands. However, there is also a sizeable informal market that remains largely unregulated.

The global correction in rice prices has led wholesale rice prices in South Africa to decline from around R7 000 a tonne to below R6 400.

Van der Vyver points out that the local price decline has not fully mirrored the drop in dollar-denominated prices, due to logistics and other costs.

ALSO READ: Household food basket: prices drop, but not for core staple foods

SA maize outlook

The same supply-driven forces are evident in maize markets.

South Africa’s maize crop is estimated at between 16 million and 17 million tonnes following good rainfall, above last year’s 16.5 million tonnes.

Higher plantings and improved yields have pushed local prices lower, while international maize prices have also declined by about 10% over the past year, Van der Vyver notes.

The strengthening of the rand by around 15% against the dollar has shaved roughly R630 a tonne off local maize prices.

Wheat prices have been more resilient, supported in South Africa by an import tariff, but the international trend remains downward as global stocks rise.

ALSO READ: Modest decline in essential food prices but savings not always passed on

Cocoa and coffee

Beyond grains, other non-South African-produced commodities such as cocoa and coffee are also easing. However, as with rice and wheat, lower raw commodity prices do not automatically translate into cheaper products at store level.

“In products such as bread, for example, the raw wheat component accounts for only 20% of the final price,” Van der Vyver explains, adding that the remainder consists of processing, transport, packaging, marketing and other value-added costs.

“In highly processed goods, such as chocolate or coffee, the raw commodity is an even smaller share of the final price.”

Logistics costs, storage, transport, port charges and inefficiencies that escalated during Covid have become a much larger component of food pricing. This means the flow-through of lower commodity prices to supermarket shelves is only happening gradually and partially.

This article was republished from Moneyweb. Read the original here.