NEWS

How Benni McCarthy saved hard-nosed Cape Flats gangster’s life

Published

3 years agoon

By

SA LIVE NEWS

Fear grips me when Eddie ‘Bok American’ Adams’ friend Yolanda January sends me her Cape Flats live location for our interview. Sensing my anxiety at his mention of Hanover Park, Adams’ cousin Balla Davids offers to facilitate a ‘safer meeting place’ as long as it’s not 50km away from the Mother City.

But, just as I am picking up a rented vehicle at the Cape Town International Airport [on a Monday], Bok’s cousin calls to let me know the man I’ve travelled to see all the way from Johannesburg has not been home since Saturday morning.

However, minutes later, Yolanda indicates he would be at her house at 9 am for our 10 am appointment. It then means I have to drive to the infamous Cape Flats.

I’ve heard and read so many spine-chilling stories about the Cape Flats. In the depths of my mind, I have a picture of a community living in a real war zone. My anxiety is backed up by meticulously recorded crime statistics by various NGOs and the South African Police Service.

A few days prior, as I was researching the story, I’d come across some hair-raising stats collated by Bright Life Foundation showing just how dangerous living there has become. Between January and September 2021 – in an area of just two square kilometres – 29 people were murdered, 24 were stabbed, and there were 244 shootings.

Without a doubt, it’s a hard place – bleak, sandy and increasingly lawless. So, as I prayerfully drive from the airport, I quickly call a friend Lloyd Gabriel who resides in Cape Town, hoping he would calm my fears about the area.

Lloyd is shocked that I’m walking right into the lion’s den – the dreaded Cape Flats – to interview the man who discovered Benedict Saul McCarthy, otherwise known as ‘Benni’.

His advice is, “when you get there, just pick him up and drive to Claremont; it’s safer there”. I heed Lloyd’s advice, and as soon as I arrive at the location, I call Yolanda because Bok does not own a cellphone. All our communication has been through Yolanda’s phone.

As soon as Bok arrives, I offer to take him out for breakfast. And once he gets into the car, I play a song I know he will love. It’s TKZee’s “Benni in the 18 area”.

Cheery, he immediately opens up and says, “Benni McCarthy saved my life”.

For those who know Adams, this would be a curious statement. For when McCarthy was a young lad growing up in Hannover Park, Adams was already a hardboiled gangster, a ruthless seasoned drug dealer leading the notorious Americans gang in the Cape Flats.

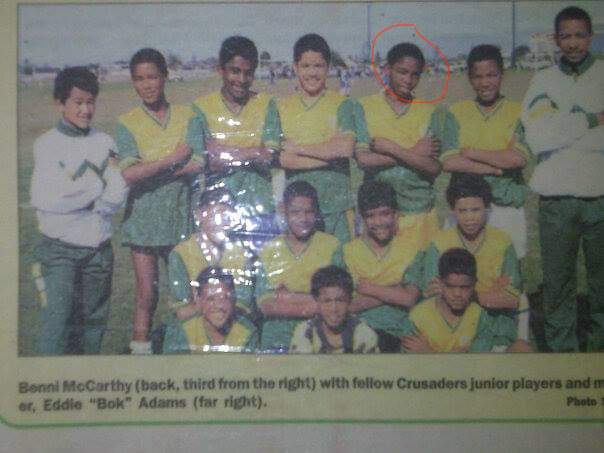

He was an apex predator in the mean and unforgiving Cape Flats, a man who never gave an inch and asked for none in return. Besides his burgeoning drug empire, Adams also ran a team, the Crusaders, for which he had once played left-back before he hung up his boots to concentrate on his crime empire. On any given Sunday, when he was the leader of The Americans, the Cape Flats turned into a dreaded warzone.

In broad daylight, bullets would fly, knives would slice flesh, and lives would be lost. And such was the case one fine Sunday, as a turf war boiled over, with gangsters laying siege on every inch of Hanover Park, waging an unholy war on a day usually reserved for praise and worship.

“My gang was The Americans,” Adams tells FARPost as he shows off tattoos of the Americans’ trademark symbol – the American flag. “The other gang was the Backstreet Kids from across the field in Hanover Park. It was a fight for territory. We were fighting each other as gangsters – bullets flying around, knives – and it was on a Sunday. The cops came and dispersed us with teargas. So, I went to sit in that corner [pointing to the exact spot] while the cops were still loitering around to make sure we didn’t start again.”

At that moment, as he took a breather from street brawls, Adams saw 15-year-old McCarthy. While he waited to renew hostilities with the Backstreet Kids, his watchful eye spotted a gangly youngster nearby, effortlessly slicing through the feeble defence mounted by his three friends who chased him around despairingly, unable to get anywhere near him.

“While sitting there, I saw these four boys playing football. Benni was one of those boys. The three were marking him, and he would dribble each of them. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. The boy had so much talent,” he says.

Adams knew that he needed McCarthy on his beloved Crusaders from that moment. He knew he had unearthed a gem in the middle of a raging gang war. It was a discovery that he believes changed his life forever.

“That saved my life because if I had continued with the gangster life, I’d have died. Football distracted me. I’d been involved with Americans for many years. So, that’s why I tell people that Benni saved my life. I played football when I was younger and stopped chasing the gangster life after seeing Benni; I was captain of Crusaders at some point. I stopped playing soccer in 1982 and got busy with gangster life; I saw Benni 10 years later in 1992,” he explains as we settle down at Rodeo Spur in Claremont, one of the so-called “Southern Suburbs” of Cape Town.

However, getting McCarthy to play for one of the most notorious gangsters in Cape Town would not be easy. The name ‘Bok American’ struck fear in many a Cape Flats boy’s heart, and McCarthy had already seen first-hand the destruction wrought by gangsters. No one might have known it back then, but South Africa was only a stray bullet away from losing its best-ever centre forward.

“I was later told that when Benni was 11, his best friend, Reginald, was shot by mistake while playing football,” Adams reveals. “Apparently, Reginald was super talented and would have gone very far. They say he was swift and skilful.”

Unfortunately, little Reginald never lived to see his 15th birthday. Despite McCarthy’s misgivings, Adams was prepared to pull a few strings to make the move happen.

“I was a gangster selling Mandrax, and people often bought my drugs because they knew I had to sustain the team,” says the 55-year-old. “I promised Benni I would pay him R1000 for every tournament we win. It was a lot of money back then in 1992. Remember, I didn’t know the boy; I just said to him, ‘don’t you want to play for me?’.

While no contracts were to be signed with gangsters sponsoring their teams, McCarthy tells FARPost that the money he received from Adams was more than his mom’s monthly income.

“If it weren’t for that man, I wouldn’t be here [in terms of football achievements],” McCarthy says on the sidelines of a Heineken event in Johannesburg recently. “The gangsters would look for the best talents at the Cape Flats to dominate the league. I was given permission to play for Bok by my dad. The money he offered me was almost the salary of my mom. That’s where people saw me playing football.”

He remembers the so-called ‘Gangster League’ fondly. In a violence-torn Cape Flats, Sundays when gangster league matches were played felt like a breather, a moment for the people of Hanover to catch their breath before violence broke out again 24 hours later. On Monday, the bloodletting would resume.

He is convinced that ‘playing against older men’ made him mature faster. He adds that the violence paused on a Sunday to make way for ‘The Bundesliga’, as the tournaments were often referred to. ‘Bundes’ were blocks between the rival gang neighbourhoods where opponents dared to go.

“Our team wore Brazil’s kits and had players who were already established. The drug lords had enough money to let us share the money we won as players. It was big money,” Nassir Benjamin, who captained the Crusaders, tells FARPost from the comfort of his Cape Flats home.

Diski was the universal language in Hannover Park, northwest of the coastal city. Most gangsters loved football. There was no love lost when fighting, but there was deafening silence on a Sunday.

“There was total silence on a Sunday; the only noise you’d hear was the celebrations,” McCarthy recalls.

Benjamin, who was also McCarthy’s childhood friend, remembers how well Adams took care of his charges, fully aware that their sleek Samba Boys’ kits and gear were all from the proceeds of crime.

“Football was important for us; Bok provided for us,” Benjamin adds. “Some of us didn’t have food at home; Bok used to sell drugs, so that’s how he was able to take care of us who played for him. If you didn’t have shoes, he’d buy them for you. We all looked alike; Bok would get us a nice tracksuit each.”

While teenager McCarthy was always a sleek and mesmerising forward in the gangster leagues, where need sometimes decided which part of the field a player ended up in, he would sometimes guard goals, where his lanky frame was a distinct advantage in penalty shootouts.

“I thought Benni was best in the middle of the park,” says Adams. “He was more of a number 10. But he could play in any position, including goalkeeping. He was tall and thin and one of my team’s youngest. Of course, there were better players in my team.”

During those days, McCarthy’s partner-in-crime, Benjamin, shares how the young forward had a naughty side off the pitch and sometimes got himself into trouble. In the same way, he seemed to wiggle away from defenders’ attention in his career; he used to evade whoever was pursuing him.

“We were very mischievous; we would steal apples from the farms. We would catch trains to the farms and fill our bags with fruit. If you got caught, then the farmers beat you up. They would put you in a room and hose you down. They’d say: “Tell your friends this is what they get if they come to our farm!” We rarely got caught, however. We were too quick,” says Benjamin.

Part Two of this story will be published on Wednesday, 3 August 2022.

RELATED STORY: What Benni McCarthy said about Manchester United

Source Link How Benni McCarthy saved hard-nosed Cape Flats gangster’s life